English

English education emphasizes the individual student’s four-year journey toward becoming a competent reader and writer. Students engage in reading and analyzing essays, poetry, plays, graphic novels and literature, both modern and classic. Our teachers have longstanding academic freedom in selecting texts and designing courses. This expertise and personal touch shows in our especially eclectic elective offerings.

At Maybeck, students take four years of English. English Composition, Intermediation Composition, and English Literature make up the first three years of programming. Our seniors round out their English requirement through a variety of semester-long English electives.

Required Courses

Core English Courses

Advanced English Electives

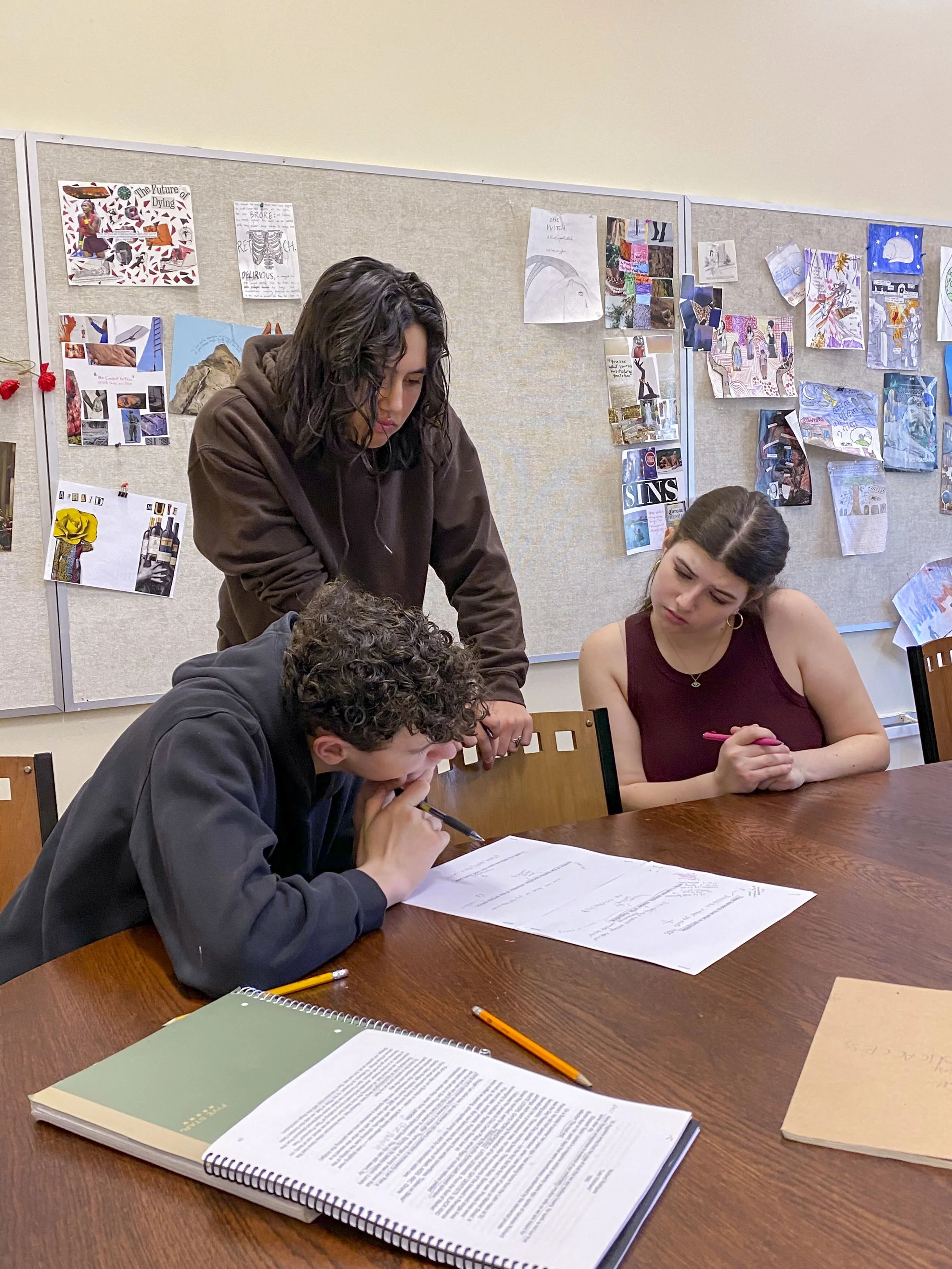

Sample English Activities

Our students are steeped in “writing-based classroom pedagogy”

Our English and Social Studies electives covering immigration took a cross-curricular approach to their content, including a trip to Berkeley Rep to see the play Mexodus.